Raymond's Weblog^

All time greatest eigenvectors

Brief intro to eigenvectors

Formally, for a given linear transformation, its eigenvectors are the vectors that get scaled up by a constant. A linear transformation is a way of mapping all the points in a space so that, if some points form a straight line in the original space, they’ll be mapped to points that also form a line, and the point in the centre doesn’t move. In 2 dimensions, the only linear transformations are combinations of stretching and rotating things.

The eigenvectors here are basically the lines which start from the centre and are just stretched or squeezed by the transformation. So in fact, they’re effectively also the lines along which you’re doing the stretching. There’s a good introduction here by 3Blue1Brown which covers the maths.

But this post isn’t an introduction to what eigenvectors are. It’s about what they’re for, why they might be interesting, and why someone (like me) would actually find them aesthetically appealing or, dare I say it, beautiful.

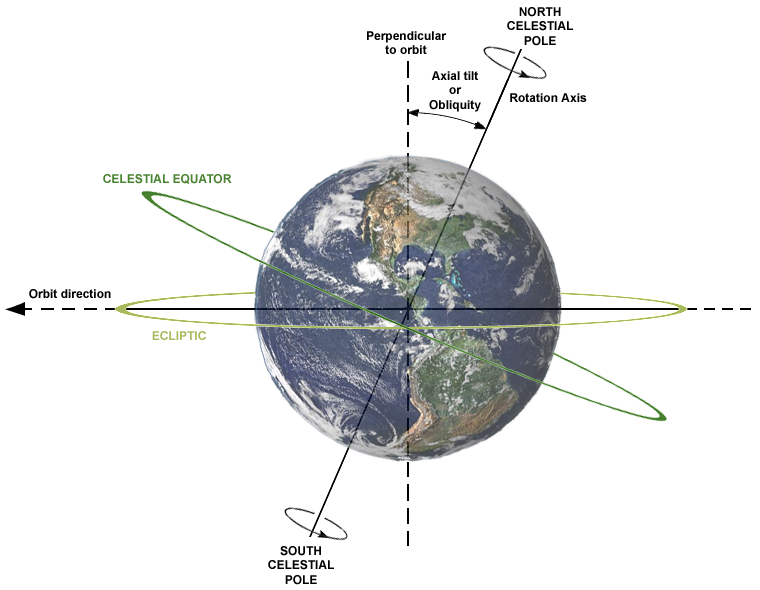

5 - The Earth’s Axis

I love all rotational axes, but this one is my favourite, because I rely on it so frequently.

Appreciating that the axis we spin around is an eigenvector was the point where I started to get a

feel for why linear algebra might actually be useful. It takes maths up to higher dimensions, and there are all

kinds of things which just don’t have one-dimensional analogues. The only one-dimensional linear transformation is

scaling, which is too simple to have many emergent structures.

Appreciating that the axis we spin around is an eigenvector was the point where I started to get a

feel for why linear algebra might actually be useful. It takes maths up to higher dimensions, and there are all

kinds of things which just don’t have one-dimensional analogues. The only one-dimensional linear transformation is

scaling, which is too simple to have many emergent structures.

At two dimensions you get things like lines of symmetry: also an eigenvector. If you ever look at a flat mirror you’re looking at an entire plane of eigenvectors. At three, you get axes of rotation.

4 - e^x

Yes, Euler’s number, a transcendental number that just seems to show up everywhere. You’ve seen it in investment banking, you’ve seen it in complex analysis, but did you know that the humble e is also an eigenvector?

You can define a vector space over any field which has as its (infinite) basis vectors the powers of some variable X. The vectors will be whatever polynomial you’d care to name. The downside is that you can’t really use matrix multiplication to multiply your polynomials, but what can do with it instead, weirdly, is differentiate.

Polynomial differentiation basically amounts to breaking the polynomial into powers of X and then multiplying them by a fixed integer and shifting them down a place. You take the coefficient of X3, multiply it by 3, and that’s the new coefficient for X2. In other words, you want a matrix where the nth row is empty except for the n+1st column, which is n+1. So it’s an offset diagonal. And this matrix will do differentiation for you.

I know what you’re thinking, what you’re positively clamouring: does it have an eigenvector? Yes, yes it does. One way you could try to work out this eigenvector is by hand. The other would be to ask yourself what polynomial, when differentiated, is at most linearly scaled. Either way you’d get an infinite expansion where the coefficients are the reciprocals of factorials - in other words, e^x.

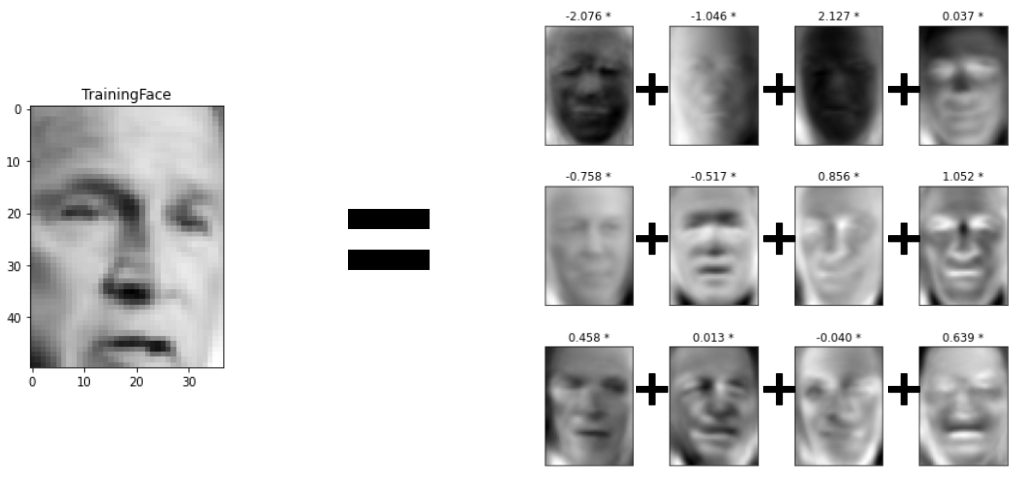

3 - Eigenfaces

One of the more unsettling things to emerge from developments in facial recognition is the Eigenface. Facial recognition, like all machine learning wizardry, involves putting things in very high dimensional vector spaces and then doing something involving probability. If you do something particularly unsettling to the covariance matrix you get something like a set of basis vectors for human faces.

It turns out that linear combinations of not that many eigenfaces can approximate any picture of a face pretty

reliably. This means you can very efficiently store enormous databases of people’s faces to reliably pick them

out. Terrifying, yes, but also pretty interesting.

It turns out that linear combinations of not that many eigenfaces can approximate any picture of a face pretty

reliably. This means you can very efficiently store enormous databases of people’s faces to reliably pick them

out. Terrifying, yes, but also pretty interesting.

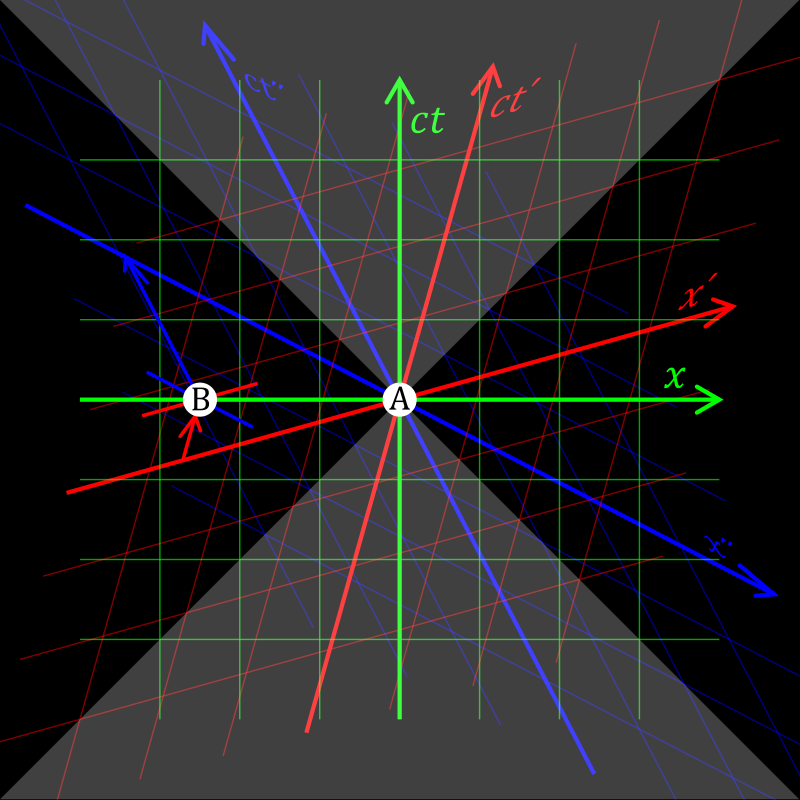

2 - Lightcones

There’s no chance I’m gonna be able to express this succinctly because it’s nuts and weird. I offer this with no justification.

Basically most people’s intuitive sense that spacetime has a future, and a past, and this thin slice in the middle that we call the present, gradually shifting forwards, is totally wrong. The reason is that once you start moving quickly it warps time around you. Thanks, Einstein.

The good news is there’s something a bit like the thing you’d want there to be: you can trace out a pair of four-dimensional cones coming out of any point in spacetime, stretching into the past and the future at the speed of light: lightcones. They represent every point in spacetime that can causally affect you, or that you can causally affect, respectively. These keep the nice transitive properties of time: the past-lightcone of a particle in spacetime contains the past-lightcones of the particle at every previous moment in time, and so on. Everything outside the lightcones is a temporal wasteland though. Whether those points in spacetime are in the past or the future is entirely dependent on how fast you’re moving.

The way that you make transformations in spacetime to translate between different frames of reference is the

Lorentz Transformations in Minkowski Space (which is bizarre by the way - turns out time is basically imaginary

space) and the eigenvectors of the Lorentz Transformations are, of course, the lightcone.

The way that you make transformations in spacetime to translate between different frames of reference is the

Lorentz Transformations in Minkowski Space (which is bizarre by the way - turns out time is basically imaginary

space) and the eigenvectors of the Lorentz Transformations are, of course, the lightcone.

How does special relativity warp spacetime? By stretching the lightcone.

1 - The Eigenvectors Of Your Favourite Diagonal Matrix

I know, it’s nothing fancy, but it’s dear to my heart. Let’s take a moment to appreciate the fact that when you’ve got a diagonalisable matrix and an invertible change of basis matrix, you can exponentiate it in a reasonable length of time, and all you have to do is compute the eigenvectors.

It might not seem like much, but if not for this simple fact we would surely never have been able to build the towering transformer models which help Google to answer our questions and which will one day replace all our functions of government.